The Disintegration of Light

Most of us know Newton from his three “Laws of Motion” that we are forced to mug up in school. College folks may even know more about his discoveries including his Theory of Gravitation and the branch of mathematics called Calculus. But, before he was scientist extraordinaire, he was just a plain old guy from Cambridge (like many of my readers I hope #fingers-crossed).

During the outbreak of bubonic plague in 1665, Newton fled his college town of Cambridge and escaped to solitude in his boyhood home at Woolsthrope, England. It was here that he first carried out experiments that would reveal a lot about the universe around us and lead to his famous unravelling of Gravity and Motion. But first, he carried out some simple experiments in optics while tinkering with a prism picked up at a local fair. Let’s dive in deeper.

Newton’s Prism Experiment

Prevailing Knowledge

This era marked a critical time for optics. It was a time when two theories of light clashed with full force. These were:

- The Wave Theory: Light is made up of waves that travel in space.

- The Particle Theory: Light is made up of particles that are invisible to the naked eye.

Proponents of the wave theory of light believed that light is made up of waves of white light and that colour spectrum is visible when light passes through a prism because of corruption of the waves by the prism (or glass). This means the more glass light travels through, the more corrupt it will become.

Newton vigorously supported the particle theory of light and strongly believed that light is made up of particles that he called corpuscles.

The Experiment

A Simple Experiment

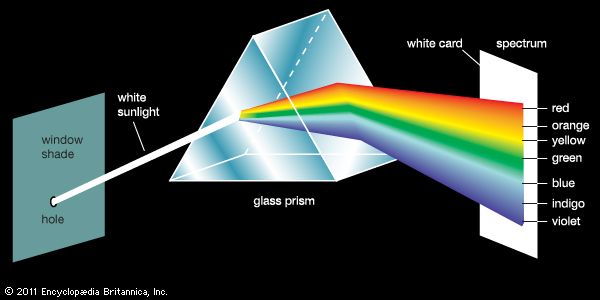

First a simple experiment was carried out where Newton passed a beam of sunlight through a prism that led to the splitting of sunlight into different colours. The setup is shown below:

Adding a Second Prism

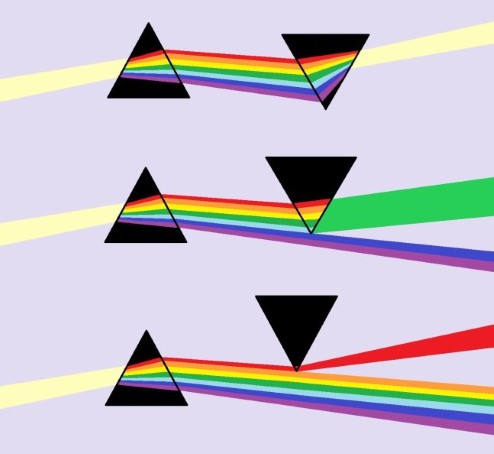

Next, Newton added a second prism to the experiment. This led to two different setups:

-

First, he isolated a single colour from the split sunlight and exposed it to a second prism. He observed that the colour did not further split into different colours.

-

Secondly, he exposed all of the colours that escaped the first prism to a second inverted prism. This led to the re-emergence of white light from the second prism.

Inferences

Newton drew interesting conclusions from the experiments. He was assured that the prism has nothing to do with the “corruption” of the light beam. As, in the case of a single colour, the beam doesn’t split any further. The second experiment led him to conclude that the beams that were emanating from the first prism were actually present in the initial beam of white light. Thus, they recombined to form white light when exposed to an inverted prism. His particle theory of light was able enough to explain the observations.

According to Newton, the prism experiment was a “crucial” experiment. A crucial experiment is an experiment that is devised to decide between two contradictory theories, where the failure of one determines the certainty of the other. Since almost everyone agreed that light must be composed of either particles or waves, Newton used the failure of the wave theory to prove that light is made of particles. Newton concluded that light is composed of coloured particles that combine to appear white.

The Spectrum of Colours

Newton first introduced the “colour spectrum”. Although the colours in the spectrum appear to be continuous without any natural boundaries, Newton arbitrarily divided it into 7 parts and called them red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet.

Newton showed that every colour has a unique angle of refraction that can be calculated using a suitable prism. He saw that all objects appear to be the same colour as the beam of coloured light that illuminates them, and that a beam of coloured light will stay the same colour no matter how many times it is reflected or refracted. This led him to conclude that colour is a property of the light that reflects from objects, not a property of the objects themselves.

Criticisms

Newton first made his claims public at the Royal Society of London (in 1672), after conducting around 44 experiments with prisms. Despite Newton thinking that his Particle Theory of light was “proven”, it faced several problems as many people who tried to replicate his findings were unable to do so. Notably, Robert Hooke claimed that the splitting of the white beam could be explained by the Wave theory of light only.

Prisms were still not regarded as scientific instruments and this didn’t really help his case. Moreover, Newton being secretive about the details of the experiment, including the dimensions of the prisms and the angles of orientation led to more disbelief. After conducting further experiments, Newton finally disclosed sufficient information in 1676 that led to successive successful trials by other scientists. Newton claimed that people who were unsuccessful in replicating his experiments had bad prisms. This led to further uproar as people saw this as an excuse. Eventually, Newton withdrew from the debate.

Light: Wave or Particle?

Soon after (1678), Christiaan Huygens proposed an improved wave theory of light that explained diffraction, refraction, reflection, and even Newton’s observations from the prism. Newton did not contribute to the debate until after Hooke’s death, 32 years after his original publication. In 1704, he was elected President of the Royal Society and published Opticks, his most comprehensive theory of light. In the opening sections of the book, Newton showed how to reconstruct his prism experiments in more detail, which led to many more successful reconstructions.

Newton also used the publication of “Opticks” to defend his stance on diffraction. To do so, he had to appeal to wave-like properties and argued that particles of light create waves in the aether. After the publication of Opticks, Newton’s theory gained considerable popularity but some of his critics remained unconvinced.

There was one way to prove which theory is correct: if light is composed of particles then it should travel faster in a denser medium, but if it’s composed of waves, then a denser medium should slow it down. This experiment would not be conducted for another 150 years (Let’s reserve that for another post someday), but by the end of the 19th century (spoiler!), both theories would be proven wrong.

The Takeaway

This post is not just about a random experiment, but also the background of the origins of the experiment. The circumstances that led to Newton’s brilliance and discoveries is not unlike the current pandemic situation around us. With the spread of coronavirus imposing isolation on people across the globe, Newton’s miracle year is being touted as a model. But don’t take it too seriously or get in a stressful mode comparing your accomplishments with that of Newton.

It is not necessary to lock up yourself in a room and concentrate on doing things “right” or getting things “done.” Great ideas (like the theory of Gravitation, or prism experiments) don’t require tedious amounts of work with sustained attention and hard thinking; they arrive in lightning bolts of inspiration (the falling apple for Newton, or playing around with prisms), which in turn come only in the right circumstances (and if you are open enough to see them), like enforced isolation during a pandemic. So, open up your ears and listen, as your creativity tries to speak to you.

Comments