On the Origins of Genetics

Most of us look somewhat like our parents, don’t we? It can be just a passing resemblance or a full blown mini-me. But have you ever wondered why? A 19th century monk first answered the question with a full blown 7-year experiment.

Mendel’s experiments with peas

A Bit of History (Coz, Why Not?)

Johann Gregor Mendel was born in 1822 in what is now Czech Republic. Although his family had little money, he showed a knack for the physical sciences. In 1843 he joined the Augustinian Abbey of St. Thomas in Brno. His interest led to him teaching science courses to students in the monastery. In 1856, he started his (almost) decade long work on inheritance patterns in honeybees and plants. Sometime later he focused mostly on pea plants (as they were easier to study/maintain compared to the honeybees). In 1865, he presented the results of his experiment on about 30,000 pea plants to the local natural history society. In 1866, he published his work, Experiments in Plant Hybridization, in the proceedings of the Natural History Society of Brünn. Here is the link to the published work for interested people.

Prevailing Knowledge

Before discussing the experiment, it is very important to understand the prevailing knowledge at that time. Scientists (and philosophers) believed in what was called blending inheritance. The theory of “blending inheritance” states that

the progeny inherits any characteristic as the average of the parents’ values of that characteristic.

Thus, most people used to believe that crossing a red variety of flower with a white variety of flower of the same species would lead to a plant with pink flowers.

The Experiment

Why Pea?

People speculate that Mendel got the idea for his crosses by initially crossing to get newer colour combinations and varieties of flowers. He got repeatable results that suggested some law of heredity at work. Mendel’s seminal work was accomplished using Garden Peas (Pisum sativum) to study the natural laws of inheritance.

Pea plants are naturally self-fertilizing, meaning the pollens encounter ova from the same flower. The flower petals remain sealed to prevent any other pollen from fertilizing. This results in highly “in-bred” or true-breeding plants. These true-breeding plants and their progeny show the same exact features/characteristics. The garden pea plants also mature in one season, meaning that several generations could be evaluated on a small stretch of time.

Hybridization Experiments

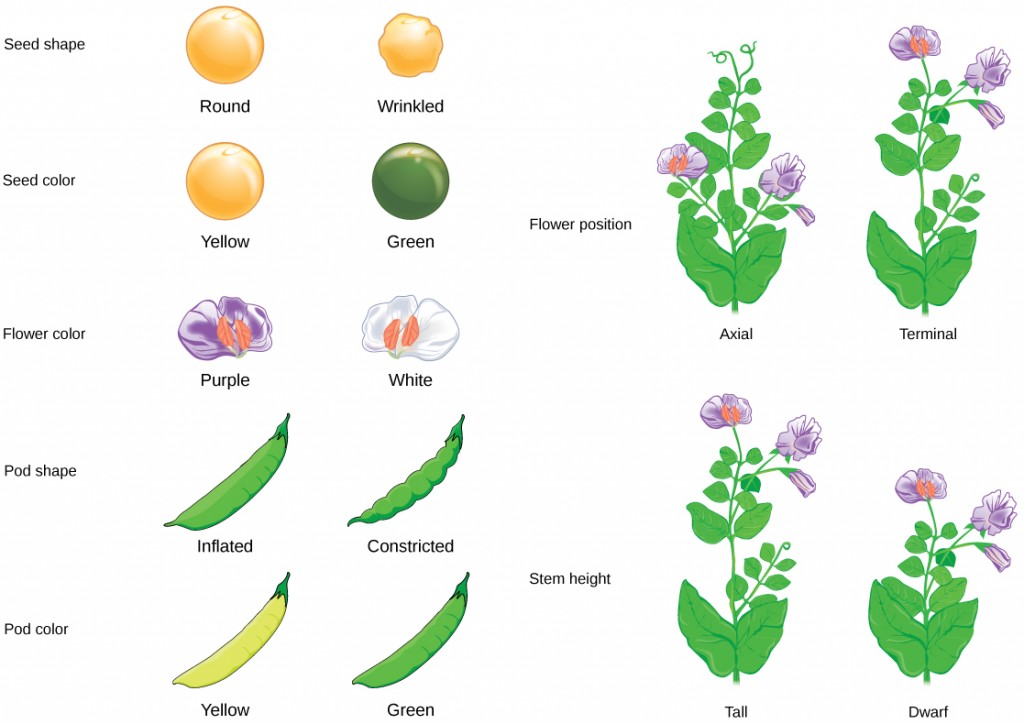

Mendel performed hybridizations, which involve mating two true-breeding individuals with different traits. A trait is defined as a variation in the physical appearance of a heritable characteristic. For example, the characteristic known as “height” broadly has two traits, “tall” or “short”. In the pea plant, hybridization is done by manually removing pollens from the anther of donor plant and “dusting” (or sprinkling) them on the stigma of recipient plant.

The Setup

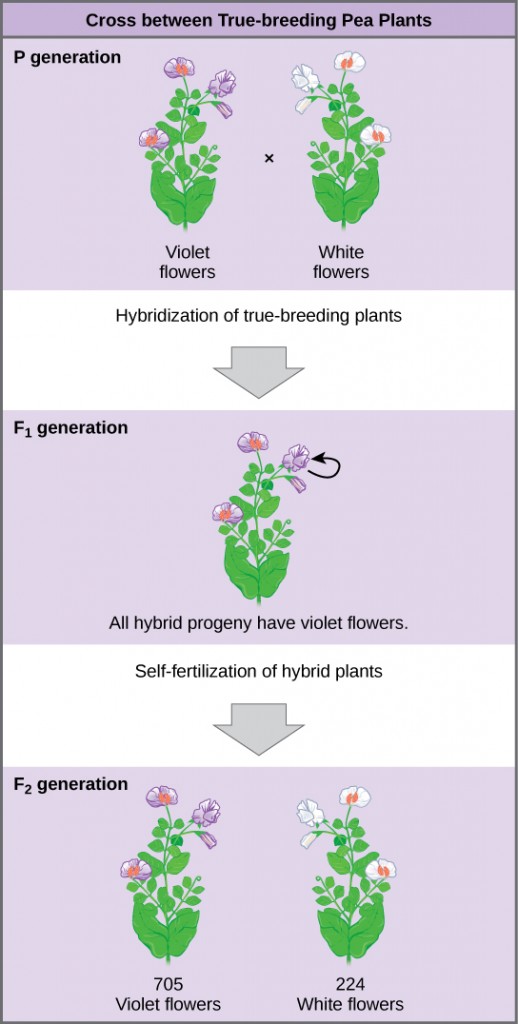

Plants used in the first generation of crosses were called P, or Parental generation, plants. Mendel collected seeds resulting from the cross and grew them the next season. These offspring were called the F1 generation, or the First Filial generation (filial = daughter or son). Once Mendel examined the characteristic of the F1 generation, these plants were allowed to self-fertilize naturally. The next generation obtained was called the F2 generation (or the second filial generation). Mendel’s experiments extended well beyond the F2 generation, but it was the ratio of characteristics in the P, F1, and F2 generation that were the most intriguing and became the basis of Mendel’s postulates.

A Variety of Characteristics

In his publication, Mendel reported the results of his crosses involving seven different characteristics, each with two contrasting traits. The characteristics included plant height, seed texture, seed colour, flower colour, pea-pod colour, pea-pod size, and flower position. The image below shows each characteristic accompanied by the contrasting traits found for the same.

To fully examine each characteristic, Mendel used large numbers of F1 and F2 plants and reported results from thousands of F2 plants.

Results

As you may have noticed in the figure above, the cross between the violet and white flowers resulted in a F1 generation with all violet flowers. This is in direct contrast to the predictions of the blending theory, which would suggest that the flowers should be of some intermediate colour. Mendel’s results demonstrated that the white colour of flowers completely disappeared in the F1 generation.

Importantly, Mendel did not stop there. He allowed the F1 generation plants to self-fertilize and found that 705 flowers in the F2 generation had violet flowers compared to 224 plants with white flowers. This converts to a ratio of 3.15 violet flowers to 1 white flower, or approximately 3:1. When Mendel transferred pollen from white flowers to violet flowers and vice versa, he observed that the same ratio was obtained irrespective of which parent - male or female - contributed which trait.

This is called a reciprocal cross - a paired cross in which respective traits of male and female in one experiment become the traits of female and male in the other cross.

For the other six characteristics, Mendel found out that the F1 and F2 generations behaved in the same way. One of the two traits would completely disappear in the F1 generation, only to reappear in the 3:1 ratio in the next (F2) generation.

Mendel’s Insights

Upon compiling all the data, Mendel concluded that the traits can be separated into two categories, expressed traits and latent traits. Traits that disappeared in the F1 generation were known as recessive traits (latent) and traits that appeared in the F1 generation were known as dominant traits (expressed). In the cross outlined above, violet colour of flowers is the dominant trait and white colour of flowers is the recessive trait.

The fact that recessive traits appeared in the F2 generation, indicate that the traits remained separate (and were not blended) in the plants of the F1 generation. To explain this apparent phenomenon, Mendel proposed that plants contained two copies of trait for the flower-colour characteristic, and each parent transferred one of the two copies to their offspring, where they came together. Moreover, the physical observation of dominant trait could mean that the organism contained at least one dominant version of the characteristic, while recessive plants contained two recessive copies of the characteristics.

Mendel Was Largely Ignored

When Mendel published his findings in 1866, they were largely ignored by other people and scientists alike. Possibly because it was ahead of its time with concepts such as discrete variation (more on this later) and statistical (quantitative) interpretation of biological data. In the early 1900s, three biologists, Hugo de Vries, Carl Correns, and Erich von Tschermak “re-discovered” Mendel’s experiments and thus, modern genetics was born. Unfortunately Mendel was not around to receive recognition as he died in 1884.

Aftermath

“Mendelism” gave rise to important but controversial developments in genetics. The most vigorous proponent in Europe was William Bateson, who coined the terms “genetics” and “allele” to describe many of Mendel’s tenets. Mendelism implied that heredity is discontinuous, i.e., a characteristic can be either black or white, there is no grey area. In contrast most of the variation that we see around us is continuous, humans have heights with very different values ranging from 3 feet to over 7 feet at times. This led to people believing that the theory worked specifically for some given species.

However, later work by statisticians and biologists (notably Ronald Fischer) showed that if multiple Mendelian factors were involved in the expression, they could produce the diverse results observed. Thus, Mendelian genetics was shown to be compatible with Darwin’s theory of natural selection. This was a major breakthrough as blending theory was never compatible with natural selection. In fact, Darwin at some point suggested that hybridization experiments led him to discover this in compatibility.

Mendel was quite ahead of his time, formulating theories based on statistical experiments (in biology) was unheard of at that time. One drawback was that Mendel did not pin point or say about the molecular basis of traits. Later scientists (Thomas Hunt Morgan and his assistants) combined Mendelism with the “chromosomal theory of inheritance” to create what is now known as classical genetics.

A Sound Experiment?

Even the most simple arrangement like initially starting out with just true-breeding varieties or having a large enough sample size is a major point that leads to credible data. He had the foresight to follow up with successive generations (F1, F2, F3, F4) and record their variations. Finally, he conducted test-crosses (hybridizing F2 generation with the P generation) to reveal the presence and proportion of recessive traits.

The marvel of Mendel lies in the impeccable experimental design that is guaranteed to provide a stockpile of mathematically sound data. Which can be used to gain insights into unseen forces and processes of nature.

It is something that we, as scientists, should always strive for.

Comments